Roger is a reader. A big reader. Tom Clancy, Harlan Coben, Lee Child, The Wall Street Journal, and many others are pleasant companions of his through life.

As a Kids Hope Mentor, Roger wonders about reading aloud to his mentee, Zion. Would Zion get as carried away with stories and information about the world as he does?

While Roger has a general sense that reading together would be fun, he fears that he should be more proactive with his limited mentor-hour time. Should he sacrifice any of their quality time on “just reading aloud” while Zion also needs support with schoolwork, for instance?

If Roger knew the power of the read aloud on achievement, these doubts would likely disappear.

Reading Aloud Builds Reading Achievement and Much More

As I noted in last week’s first post in this month’s series in honor of National Literacy Month, reading aloud–has been called the “single most important activity for building the knowledge required for eventual for success in reading” (from a national report, Becoming a Nation of Readers).

Bold claims like that from researchers may surprise you, like Roger. Let’s dive a little deeper into the why’s and how’s of the read-aloud’s impact on reading achievement. This reading achievement goal is important to consider as reading achievement relates to almost every aspect of school success–and beyond.

Oral language is the backbone of reading achievement. We need to know the words, ideas, and concepts that an author refers to in order to comprehend her text well. For instance, I’m generally a “good reader,” but my reading comprehension of a mechanical engineering text would be pretty poor because I know so little about that entire domain.

Similarly, children’s limited experience with the world hinders their reading comprehension. If an author alludes to the Civil War, but the child has never heard of the Civil War, then that child’s comprehension of the text is likely to suffer.

However, when we read aloud to children, we pass along a rich “database” of oral language. The more children are read to, the more their oral language expands: The fiction book utilizes words that are rare in everyday speech. The nonfiction book teaches concepts and vocabulary in its respective field of, say, science, history, or culture.

Researchers have revealed how written language surpasses speech in building oral language skills (which build reading comprehension). For instance, even simple children’s books often use more sophisticated words than typical conversations among college-educated adults.

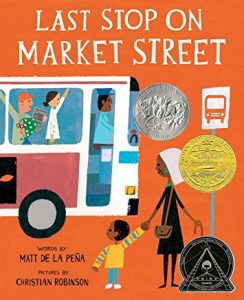

Consider the sweet, simple text of The Last Stop on Market Street, by Matt de la Peña, which won the Newbery Medal. Though there are few words on each page and the main audience is young elementary students, we hear words and turns of phrase that are uncommon in everyday speech, as in,

“The bus creaked to a stop in front of them.

It sighed and sagged and the doors swung open.”

As a child goes about her day at school and at home, she’s unlikely to hear another person speaking to her with words such as “creaked” and “sagged.” She’s also not likely to hear an extended metaphor of a bus sounding like a tired, old person, who “sighed and sagged.”

This brief example offers a glimpse of how our written language yields so much more advanced vocabulary, concepts, and phrases, above and beyond what can be heard in everyday speech.

Oral Language Gaps Explain Much of Our Achievement Gaps

Roger, and you, may be uniquely poised to help enrich this oral language domain for our precious mentees, who may be less likely to have the strong language skills needed in order to thrive in reading, and school in general.

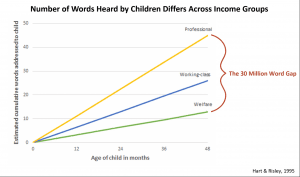

Researchers have stunned the world by demonstrating how vast the gap just may be–between the oral language “have’s” and “have-not’s.” In one well-known study, researchers recorded conversations between pre-school children and their caregivers and counted the numbers of words spoken in each household. This work revealed that by age 4 there could already be a gap of 30 million words between the words heard by children in families of professional backgrounds, as contrasted with those in families receiving welfare.

Whether the gap is 4 million or 30 million, numbers of words heard and conversational turns taken are clearly related to vocabulary achievement. According to estimates, some of our 1st grade students may have a word bank of about 2,500 words whereas others in the same class may have closer to 10,000 words learned (see more).

Read Aloud to Build Oral Language and Reading Achievement

Access to words–and lots of them–is how oral language achievement it gained. Perhaps some of our mentees do lack a rich oral language?

What’s the most efficient and powerful tool to expand oral language?

Reading aloud!

As Roger pulls aside his young mentee and reads to him from Winnie the Pooh, he not only builds emotional bonds and models a love of literacy, he is likely exposing Zion to sophisticated words and concepts he may not hear anywhere else. Zion might learn words and phrases, such as “growly,” “slithered,” “wedged,” and “under the name.” He might also learn more about the woods and bees and friendship.

And, over time, these deposits of words and ideas gather into a growing bank account of oral language. As a result, Zion will comprehend more and more texts he’s expected to read in school and will have a greater awareness of this great big world.

How about you? What deposits of oral language might you make this week with your student?

Test drive one of these favorites, perhaps:

Dr. Marnie Ginsberg is a literacy specialist and consultant who has worked as a classroom teacher, university reading researcher, reading tutor, and school staff developer. When she was a middle school teacher, she read aloud almost every day to her students and it was the best part of the school day. She developed the KHUSA Read Together program and also supports Kids Hope mentors who are trying out Read Together components.